Vancouver Island’s hereditary chief Bill Wilson, who reshaped Indigenous rights across Canada, dies at age 80

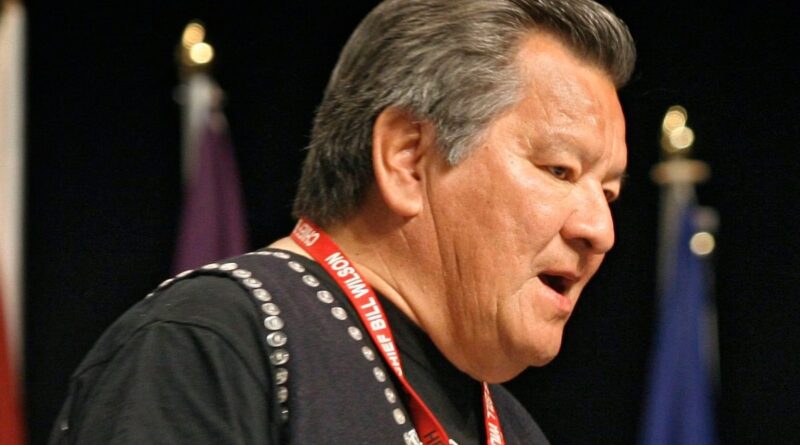

Bill Wilson, a hereditary chief and the father of former cabinet minister Jody Wilson-Raybould, has died.Jeff McIntosh/The Canadian Press

Bill Wilson, the fiery hereditary chief from Vancouver Island who helped ensure Indigenous title to traditional lands and treaty rights for both men and women were enshrined in Canada’s Constitution, has died at the age of 80.

Former federal attorney-general Jody Wilson-Raybould announced the Friday death of her father.

“His life was one of leadership and striving to make change … and change he did make,” she wrote in a post on X. “He taught us well, and we strive to honour all he gave us by carrying on his work.”

Mr. Wilson stepped into the national spotlight in 1983 as the spokesperson for the Native Council of Canada at a conference with the country’s first ministers, where constitutional changes dealing with Indigenous rights and title were on the table.

“I know that there are people here at this table who are more concerned with protecting the power they have, the jurisdiction they have, than making sure that the lives of Native Indian, Inuit and Métis people across this country are improved,” he said as he stared down then-prime minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau across the room.

“A change in attitude among all Canadians must solve this problem.”

The amendment secured at that conference to Section 35 of the Constitution recognizes and affirms existing Aboriginal rights – a hard-fought inclusion that secured near-unanimous support among the provinces. While Sec. 35 does not explicitly define those rights, it has provided the basis for most title cases in the past 40 years that have shifted the legal landscape and rights and recognition in Canada.

Mr. Wilson, born in the Vancouver Island community of Comox in 1944, came from an influential family of activists among the Kwakwaka’wakw tribes of northern Vancouver Island. His grandfather was a storied medicine man. Ethel Pearson, his mother, was a respected force within the Kwak´wala culture who brought her young son along on the front lines when she protested for her nation’s rights and title.

When Mr. Wilson was a child, his father was able to keep him out of residential school, even as some of his relatives were sent away. As a boy, he displayed an early talent for questioning authority.

In a Facebook post in 2022, Mr. Wilson recalled how he was kicked out of Sunday school at St. Peter’s Anglican church in Comox when he was seven years old for speaking his mind.

“Questions based on REASON were not welcome there. Never ‘learned my lesson’ and kept asking them. Cost me many associations and jobs, but that never stopped me,” he recalled.

He also helped break the deadlock in British Columbia that had stalled treaty negotiations by bringing Canada to the table through the creation of the BC Treaty Commission in 1992. B.C. Premier David Eby shared his condolences on social media.

“His powerful legacy is an inspiration for how to carry ourselves in this world,” he wrote.

Mr. Wilson was the second Indigenous person to earn a law degree from the University of B.C. and he firmly kept his feet grounded in his culture. Mr. Wilson’s title as a hereditary chief, Hemas Kla-Lee-Lee-Kla, reflects his high rank in the community.

Rick Johnson, who is both an elected and hereditary chief of the Kwak´wala, grew up alongside Mr. Wilson, and said on Sunday that he said fulfilled his purpose, as his mother had taught him: “She always said to Bill, ‘you were given a gift to lead your people’.”

Not only did Mr. Wilson help reshaping Indigenous rights across Canada, Mr. Johnson said, but he influenced younger generations to fight for their culture.

Both his daughters, Jody and Kory, have emerged as leaders in their own right.

At that First Ministers’ Conference in 1983, Mr. Wilson told Mr. Trudeau that his both his daughters wanted to be lawyers, and then prime minister some day. He was not entirely off the mark: Both women earned their law degrees from the University of B.C.

In 2015, Ms. Wilson-Raybould became Canada’s first Indigenous justice minister under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government. (She was later ousted from the party in the fallout of the SNC-Lavalin affair – sparked by a media report that she had faced inappropriate pressure from top Liberals over prosecution of the company.)

Kory Wilson, chair of the BC First Nations Justice Council, said in a LinkedIn post that her father changed Canada: “He is an inspiration and I am so grateful he was my dad. Each and every one of us must do what we can to make the places and spaces we occupy better. Rest in Power dad.”

On Monday, Ms. Wilson is set to be awarded The King Charles III Coronation Medal by B.C. Lieutenant Governor Janet Austin in recognition of her achievements in law, postsecondary education and reconciliation.

Mr. Wilson is survived by his wife, Bev Sellars, and his daughters.