Trump’s W.H.O. Exit Throws Smallpox Defenses Into Upheaval

President Trump’s order that the United States exit the World Health Organization could undo programs meant to ensure the safety, security and study of a deadly virus that once took half a billion lives, experts warn. His retreat, they add, could end decades in which the agency directed the management of smallpox virus remnants in an American-held cache.

Health experts say discontinuation of the W.H.O.’s oversight threatens to damage precautions against the virus leaking into the world, and to disrupt research on countermeasures against the lethal disease. They add that it could also raise fears among allies and adversaries that the United States, under a veil of secrecy, might weaponize the smallpox virus.

“I’ve been in that lab,” said Thomas R. Frieden, a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, where the American cache resides. “Imagine a submarine inside a building and the people walking around in spacesuits. It looks like something out of a movie.” To reduce smallpox risks and misperceptions, Dr. Frieden added, “we need to open ourselves up to inspection.”

On Monday, Daniel R. Lucey, a Dartmouth medical professor, posted an article on the blog of the Infectious Diseases Society of America warning that Mr. Trump’s W.H.O. exit could imperil “smallpox virus storage, experiments, reporting and inspections.”

A half century ago, the W.H.O. purged the smallpox virus from human populations after the scourge had killed people for thousands of years. Dr. Frieden called it “one of the greatest accomplishments not just of medical science but global collaboration.”

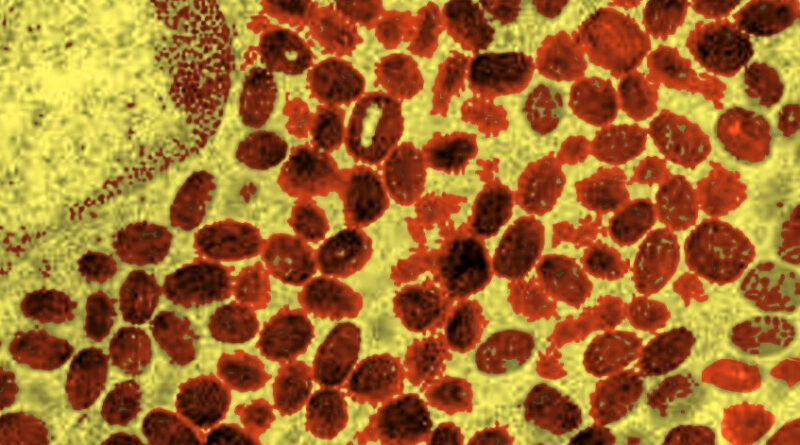

While the germ was eradicated in people, two repositories were preserved to allow study of the virus should it re-emerge: one in Atlanta, the other in Russia. To curb leaks, both caches are stored in special labs classified as Biosafety Level 4, the highest tier of protection.

In recent years, the W.H.O., based in Geneva, has ruled on the safety and scientific merit of proposed studies of smallpox by both the C.D.C. and its Russian counterpart. It has the authority to grant or refuse permission despite its role being described publicly as advisory. The agency also regularly inspects the smallpox labs for safety lapses.

Health experts warn that Mr. Trump’s exit from international oversight could end Washington’s ability to scrutinize Moscow’s smallpox cache. “If we want to inspect the Russian lab,” Dr. Frieden said, “we need to be part of W.H.O.”

Russia probably hides some smallpox virus for military use, according to a federal intelligence assessment. Health experts also warn that the American exit from the W.H.O. could prompt fears that the United States might weaponize the lethal virus.

In his first term as president, Mr. Trump lashed out at the W.H.O. over its handling of the coronavirus pandemic and, in July 2020, ordered a withdrawal. But six months later, before the separation could be completed, former President Joseph R. Biden Jr. reversed Mr. Trump’s decision on his first day in office.

This time around, Mr. Trump came on stronger, issuing an executive order within hours of taking office that gave notice of the U.S. withdrawal. He also told his administration to identify U.S. and global partners that could “assume necessary activities” that the W.H.O. had previously carried out.

A week later, the C.D.C. was ordered to end all collaboration with the W.H.O.

It is not clear if the W.H.O. and the C.D.C. have completely ended their smallpox cooperation. Their replies to email queries seemed contradictory, and the White House did not respond.

Christian Lindmeier, a W.H.O. spokesman, said officials at the agency were still seeking to clarify the implications of Mr. Trump’s order. The agency, he added, “is ready to work with the new U.S. Administration to sustain our vital collaboration.” The next smallpox inspection, Mr. Lindmeier added, is scheduled for May 2026.

The C.D.C. is part of the department of Health and Human Services, whose communications director, Andrew G. Nixon, said only that it was complying with Mr. Trump’s order for the U.S. to withdraw from the W.H.O.

Unlike most viruses, smallpox, known as variola, is highly stable outside its host. It can long retain its power to infect, aiding its spread. Victims develop high fevers, deep rashes and oozing pustules. About a third die. In the 20th century alone, the virus is estimated to have taken more lives than all wars and other epidemics put together.

In 1959, the W.H.O. resolved to eradicate the killer in a blitz of global vaccinations and quarantines. Little was achieved until Washington and Moscow in 1966 proposed a stronger effort. That year alone, the disease killed two million people. By 1977, the W.H.O. recorded its last case, defeating the deadly scourge.

Today, the American W.H.O. exit may raise the risk of the smallpox virus escaping confinement and reinfecting the world, some health experts say. They see that threat as implicit in how past W.H.O. inspections of the C.D.C. smallpox labs made scores of recommendations for safety and security upgrades.

The proposals included better security systems, training, risk assessments, inspections of pressure suits, accident investigations and monitoring of staff competency.

David H. Evans, a virologist at the University of Alberta, has twice inspected the C.D.C. virus area and been a member of the W.H.O.’s smallpox scientific advisory panel.

While withdrawing from the W.H.O. may not increase the risk of a leak, he said, collaboration between the U.S. and the W.H.O. works quite effectively at improving research and lowering suspicions of illicit work.

“It keeps people talking to each other,” Dr. Evans said. “It gets back to the idea of transparency. It gives you some idea of what’s going on.”

Last year, a panel of the National Academy of Sciences described the cooperative smallpox research of the C.D.C. and the W.H.O. as “urgently needed.” Looking beyond vaccines, the panel called for a new generation of antiviral drugs that would better fight smallpox in individuals already infected with the pathogen.

The W.H.O. research has had practical payoffs. Antiviral drugs developed by its smallpox program have been deployed to fight Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, which is spreading quickly in parts of Africa, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In 1996, W.H.O. members agreed on a plan to destroy the two remaining stocks of the smallpox virus. Now, increasingly, it aims to prepare for potential outbreaks rather than permanently extinguishing the virus.

But those heightened levels of defensive planning could be undone by the American withdrawal, health experts warn. They fear more countries may leave the W.H.O., spurring new outbreaks.

Michael T. Osterholm, the director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, noted that Argentina, echoing Mr. Trump, withdrew from the W.H.O. early this month, and that Hungary and Russia have also explored the idea.

“Global health safety is effective only if we have global representation,” Dr. Osterholm said. “W.H.O. will do what it can. But at some point, we’re going to have a real challenge.”

Dr. Frieden, the former C.D.C. director, agreed.

“Health is not a zero-sum game,” he said. “When one country is healthy, it helps not only them, but their neighbors and the world.” He cited the purge of the smallpox virus from human populations as a remarkable case study in the benefits of global teamwork.

“There’s no doubt that W.H.O. could be more effective,” Dr. Frieden added. “But there’s also no doubt that it’s indispensable.”