Paul Simon’s search for hearing loss cure leads him to groundbreaking Stanford Medicine program and some hope

When legendary singer-songwriter Paul Simon began to lose his hearing nearly four years ago while working on his album, “Seven Psalms,” he feared he wouldn’t be able to perform again.

“It was incredibly frustrating. I was very angry at first that this had happened,” Simon told CBS News senior culture correspondent Anthony Mason in an interview for “CBS Mornings.”

He admits one of his biggest fears was giving up what he loves: making music.

“I guess what I’m most apprehensive about would be if I can’t hear well enough to really enjoy the act of making music,” Simon said.

Since then, he’s had dramatic hearing loss, sharing that he now has about 6% hearing in his left ear. But he’s learned to make adjustments. He’s switched to larger speakers, placing them all around him when he’s playing so he can hear better. He’s also had to change how and what he plays.

“I’m going through my repertoire and reducing a lot of the choices that I make to acoustic versions. It’s all much quieter. It’s not ‘You Can Call Me Al.’ That’s gone. I can’t do that one,” Simon said, chuckling.

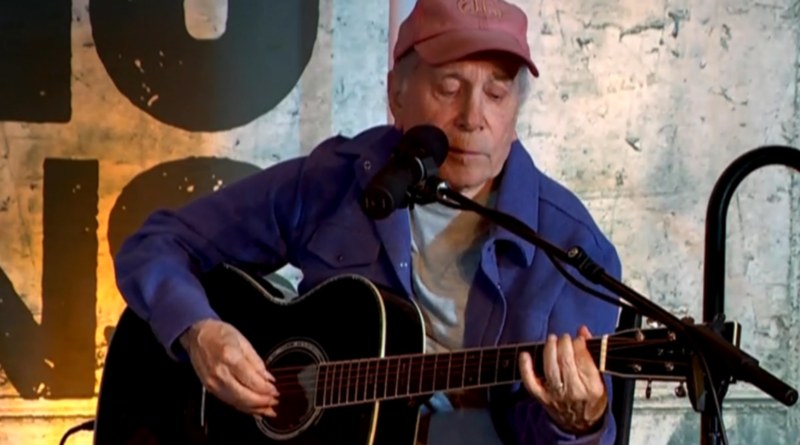

Simon is still writing music and he returned to the stage in September for a rare, stripped-down performance at The Soho Sessions in New York.

“You know Matisse, when he was suffering at the end of his life, when he was in bed, he envisioned all these cut-outs and had a great creative period,” Simon said. “So I don’t think creativity stops with disability. So far, I haven’t experienced that. And I hope not to.”

Paul Simon’s search for answers

At first, doctors told Simon there was nothing they could do about his hearing loss. Then, he learned about the Stanford Initiative to Cure Hearing Loss (SICHL), which includes a team of nearly 100 scientists searching for ways to prevent, repair and replace damaged inner ear tissue.

That’s promising news for Simon and millions like him. Hearing loss is on the rise, affecting nearly 1.5 billion people across the globe, according to Stanford Medicine.

Mason recently joined Simon during a visit to the program’s facility in Palo Alto, California, sitting in on Simon’s exam with Dr. Konstantina Stankovic.

“Hearing bones are the smallest bones in the body,” Dr. Stankovic said. “And then they are connected to the inner ear, which is called the cochlea. And it looks like a snail.”

The cochlea is so small and fragile it’s impossible to biopsy without causing deafness. It’s hidden in the hardest bone in the body, located deep in the skull, Dr. Stankovic explained.

What can animals teach us about hearing loss?

Certain animals can recover from hearing loss because their hair cells regenerate. It’s the hairs in the ear, called cilia, that transmit sound to the brain.

“We actually have the same genetic machinery, it’s just turned off in people,” Dr. Stankovic told Mason. “And the key question is how do you turn it on? And how do you turn it on safely, because cancer is regeneration gone awry.”

In a lab at the Stanford Initiative to Cure Hearing Loss , geneticist Teresa Nicolson is studying zebrafish, which have similar inner ear structures to humans.

Nicolson said they’ve made a recent, exciting discovery. They were able to rescue hearing in zebrafish with hearing loss mutations using an FDA-approved drug. The hope is it could one day be used in humans.

Down the hall, biophysicist Tony Ricci is conducting an experiment focused on mice.

“So the hair bundle is the site where most damage happens. So with aging, with noise…we are trying to understand how the bundle – like it’s a machine, right? So how this machine works normally,” Ricci said.

“So then when we know what piece’s parts are getting broken, we can figure out how do we fix it or how do we replace it,” he added.

Surgeon and scientist Dr. Alan Cheng is using gene therapy to coax the damaged hair cells in mice to regenerate. He’s also studying human cochlea samples from organ donors.

“We’re the only place in the world that can do it, in fact,” Dr. Cheng said.

The team was surprised to find that damaged human hair cells do begin to regenerate on their own, but only partially. Now they need to find out whether the drug cocktail they’ve used in mice could work in humans.

For Dr. Cheng, this research is personal.

“My mom, who has hearing loss, she’s been asking how can we regenerate cells for her,” he said.

“That’s what I’ve been asking ever since I met you guys,” Simon added with a smile.

Dr. Cheng said simply: “We’re working on it.”