Longtime neighbors deal with challenges of aging in Colorado

The white brick home sits on a quiet street in Denver’s Mayfair neighborhood, an expansive, ranch-style construction reflecting its 1950s vintage while rooftop solar panels hint at ongoing efforts to modernize since Mandell Winter Jr. and his wife, Patricia, bought the house from his parents in 1978.

A Colorado Sun series. Read more.

Colorado is getting older, rapidly. Are we prepared? We’re taking a look at how these shifting demographics are affecting housing, the workforce and quality of life, and whether Colorado has the services needed for people to age in place. Stay tuned for more reporting from this series.

Like many houses of its era, occupied for decades by the same family, it holds deep personal history. Winter’s parents had downsized and moved into the second floor of their parents’ house on Capitol Hill, a move that made so much practical and financial sense that they offered to carry the note on the Mayfair house at a then-unheard of 6% interest. It proved an offer the young couple couldn’t refuse, even though it took years to reimagine the space as their own.

Now, 47 years later, the Winters — both in their 70s and battling more frequent medical challenges — find themselves facing a conundrum familiar to many older Coloradans. As they began to consider downsizing or simply more liveable housing options to accommodate this stage of their lives, both aesthetics and economics seem aligned against them.

The Winters are anything but outliers. Mandell notes that more than half the homes on their block are owned by folks in their 70s to 90s. Some of them have been fixtures here for over 40 years, and watched their children grow up playing together.

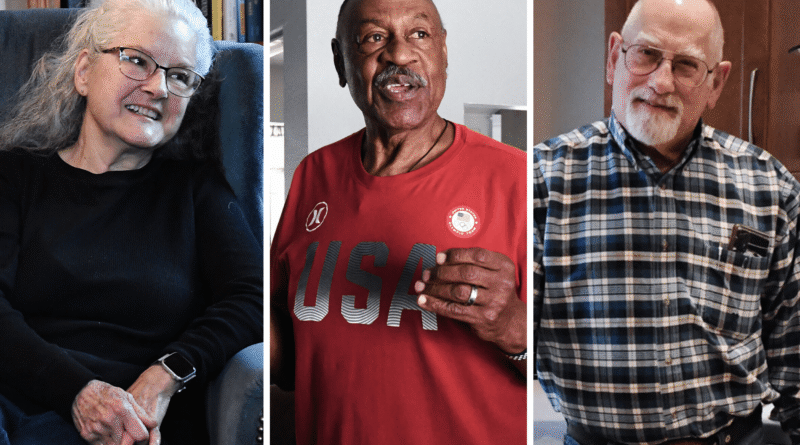

Houses that once fulfilled all their needs with young and growing families look different viewed through older eyes. For instance, Carol Phelps across the street and Will and Monetta Edwards next door are all dealing with the challenges of aging and reconsidering the viability of their homes.

And now, Colorado finds itself coming to grips with a demographic shift that projects more than a quarter of the state’s population will be over the age of 60 by 2050. Already, the state’s 60-plus population increased 22.4% between 2013 and 2023 — the most recent data available — with the median age for those residents at 69.6 — up from 68.3 a decade earlier.

But looking at the 10-year span from 2013-23, Colorado ranked third in the U.S., tied with Oregon, for the fastest growth in the over-60 population with a 1.9% jump.

In this first in an ongoing series of reports on the impacts of Colorado’s aging population, the Sun looks at a cluster of homeowners — neighbors for decades — confronting a range of common concerns, but each with their own twists.

These neighbors find themselves straddling a divide — on the one hand, they feel buffeted by a shifting post-career budget calculus, market forces and a litany of medical challenges. But on the other, even as they weigh possibilities for change, part of them remains moored to personal history within familiar walls and a comfortable community.

Their burgeoning demographic has inspired a sequence of statewide studies over the past decade. From a Strategic Action Planning Group on Aging in 2015 to the recently released Multi-Sector Plan on Aging, a collection of governmental agencies and partners in the community have examined the widely varied needs and resources of this diverse population.

The 2015 study revealed a big problem with older adult housing. The current plan focuses on solutions — actually enacting measures that could address a variety of issues, from homelessness prevention to property tax exemptions and credits, says Kristine Burrows, a senior specialist on aging for the Colorado Department of Human Services who was responsible for the creation of the Multi-Sector Plan.

“The research question we’re looking to solve for is: If we can put more funding into services that help people age in place, will that save people in Colorado money in the long run, and what’s the return on investment?” she says. “We think it’s probably pretty significant.”

The challenges touch on intersections of policy and personal narratives. On this slice of east Denver, they’re illuminated by decades of history in homes that have proven valuable touchstones — and now bring the realities of aging in Colorado into sharper focus.

Burrows notes that when it comes to housing it’s often the personal piece, the emotional side, that’s hardest to navigate. By way of example she points to her own parents and in-laws currently confronting the confluence of age and lifestyle and having difficult conversations: Do we stay in a familiar community? Move to a more vibrant neighborhood? Remain in a house shaped by lifelong investment and sweat equity? Or move to one that better accommodates shifting physical realities of age?

“I consider myself an expert in this space,” Burrows says, “and the emotions kind of overcome the expertise.”

A home full of treasures

Carol Phelps and her husband, Bob, moved into their house across the street about a year after the Winters returned to the neighborhood. They raised two girls, popped the top to create the first two-story on the block and, over several iterations of remodeling, put their indelible stamp on the house inside and out — from the unique atrium at its center, to the baby grand piano in the living room to the original pink toilet transplanted to the backyard as an objet d’art.

The Phelpses bought the house, built in 1947, for $80,000 in 1979, paying a shade over asking price in a hot seller’s market. In recent years, it has appraised for as much as $1.3 million.

But since Bob died in October of 2021, Carol, 77, finds herself stuck. On one hand, there’s her desire to surrender the responsibilities of upkeep on their nearly 3,000-square-foot dream home for the convenience of a condo. On the other, she looks all around her and sees the daunting — almost overwhelming — wall-to-wall accumulation of treasures and artifacts accrued over a lifetime.

From her upstairs bedroom, where Bob’s best neckties still hang on pegs along the wall, to his basement workspace, still overflowing with a serious handyman’s tools, a house perpetually in transition in some ways now sits frozen in time. So much … stuff.

“Some people would say, ‘They’ll just hire somebody to come and clean it out,’” Carol says. “But we can’t do that because …”

“What do we do with the baby grand (piano)?” interjects her daughter Juliana, who moved back to help with her father’s care in the late stages of his illness and stayed on. “We’re not going to get rid of the baby grand. There are things we just can’t get rid of.”

When mother and daughter talk about moving on from the home, it’s a speculative conversation — they’re both too busy to focus on a housing transition. Juliana, 44, currently works as a cloud technical consultant for an accounting firm. Carol, a physician who retired from clinical practice a few years ago, works from home as a contractor reading medical charts to help process disability applications — a job that “keeps me in the game” while also helping to cover expenses to visit her older daughter, Sarah, who lives in Germany.

“When we’re talking about aging, eventually we talk about our five-year plan,” Juliana says. “Except that every year it’s still a five-year plan.”

It’s not that Carol hasn’t considered the options. There’s an upscale senior community in Highlands Ranch that has piqued her interest. She has kidded Juliana about becoming a full-time resident on a cruise ship. But staying put in the house she and Bob occupied for so long has undeniable appeal, though she laughs at what it might take to make that a reality.

“What I really want to do, Julie, is hire a housekeeper, cook, a lady’s maid and a gardener,” Carol says to her daughter. “And if I can get those things, then I think we can stay here permanently. But we really need all the ‘Downton Abbey’ staff.”

It seems beyond her means, but if cost were no impediment?

“I think I would hire people to help and I would stay here,” she says.

Carol suffered a heart attack just a few months after Bob’s death — despite her vegan diet, careful watch over cholesterol and exercise regimen. That, combined with arthritis, back surgery and three joint replacements further slowed her active lifestyle.

“I never had any symptoms before, anything that I recognized, anyway,” Carol says of her heart attack. “So I’ve been ashamed and frightened and mad, and I’m just now coming to terms with it. I’m feeling pretty good, and I know that I’m doing everything I can, and I just keep active as long as I can.”

She stopped skiing only a couple years ago. Before that, she leaned toward black diamond runs — Pallavicini, Outhouse and West Wall are a few name-drops familiar to the initiated. She has an e-bike, but now avoids riding too far by herself. Long hikes make her “a little anxious” because of her heart, yet she has no concern for the flights of stairs she negotiates several times a day in her house and would never trade them for the single-level ease of a ranch-style home.

“I think stairs are good for you,” she insists. “I think you should embrace them.”

Helping older Coloradans recalibrate their housing needs — and then execute a strategy — looms as a multifaceted proposition that, at least in part, requires decisions in the political and policy realm, says Burrows, the senior specialist on aging. Can we reform the capital gains tax formula to make it easier to downsize? Will the recent legislative fix to the contentious condo developer liability issue boost inventory and provide more viable options?

“There are policy levers that we need to be pulling to figure out what you need,” she says, “and then there are policy levers that we need to pull to make that execution possible.”

I think stairs are good for you. I think you should embrace them.

— Carol Phelps, on maintaining an active lifestyle while having to give up activities such as skiing

Carol’s active mindset continues to drive her — reflecting one segment of a range of circumstances that define aging Coloradans. Burrows hopes to create tools to help guide older residents through the aging-in-place conundrum.

She envisions a “long-term care option methodology,” a framework for assessing people’s needs and means on the way to constructing a plan to enable them to remain in their homes or consider alternatives if that simply isn’t possible.

“Say you don’t want to necessarily leave your home,” Burrows explains, “but you need help with changing your sheets or cleaning bathtubs — normal upkeep of your house. My goal is to look at what might be possible if we could plug in your socioeconomic status and your financial status, your social needs, your health care needs, your general aging-in-place needs, and come up with a model.”

Inevitably, some solutions could be long-term care placement or assisted living, subjects that often trigger an intense, emotional response. The methodology would attempt to provide a dispassionate framework for calibrating needs, while leaving room for emotional support.

“That conversation is really challenging, because it’s often people’s homes you’re talking about, where they feel the safest,” Burrows says. “Can we help make that process easier for people right now? I don’t think we have a lot of great resources to do that currently.”

Choosing to stay or go

In the late 1960s, young Will Edwards drove west from Michigan to seek his fortune — and found it first at Northeastern Junior College in Sterling, where he made his mark on the basketball court (before finishing his hoops career down the highway at Colorado State) and met his future wife, Monetta.

In 1981, they found the perfect landing spot to raise their family — a comfortable, 1,757-square-foot ranch layout built in 1952 that featured no basement, only a crawlspace, and had some features, like a doorbell at the rear entrance, that hinted at a home once designed to accommodate a live-in maid. It offered space that Will never had growing up with several siblings back in Grand Rapids, and it reminded Monetta of her suburban Westminster roots.

They paid about $107,000.

“There was just something about the house that I just said, ‘I gotta have it,’” she recalls. “I just really liked it. I would have preferred, probably, to have a basement, even though it’s harder when you get older to go up and down. I’m thankful now we don’t.”

Will, 78, taught in the day treatment program for special needs kids at University Hospital, where in those days he could walk to work, until the program closed and he shifted to teaching physical education at a school in Montbello.

When they first moved in, Monetta, 76, worked for a cosmetics company. But after she gave birth to the second of their two sons, Chad and Larry, she took a job at the nearby King Soopers, where she worked for 18 years until her retirement in 2009.

Over the years, the neighbors — including the Winters, who live next door, and the Phelpses across the street — had block parties and yard sales where, at the end of the day, everyone could rummage through whatever remained and buy anything for a dollar. For whatever reason, neighbors don’t seem to socialize as frequently as they used to, Will and Monetta say.

Ask the couple what the next phase of their lives might look like, and you get two distinct answers.

“We’re kind of split,” Will says. “She wouldn’t mind something that’s smaller and more convenient. But I’m kind of like, ‘No, I want to be here.’”

“I would move in a heartbeat,” Monetta confirms. “I mean, I love it here, and I love the neighborhood and everything — but just for a change, you know?”

They’ve visited friends at Windsor Gardens, a longstanding over-55 development of about 3,500 residents, and she likes its sense of community.

“You know you’re not alone,” she says.

But Monetta’s physical challenges — she beat breast cancer, had knee and hip replacements, ankle fusion, plus arthritis — affect her mobility to the point that she allows that she may be “past the stage of moving” because she’s come to appreciate a home that has few steps to negotiate. She’s grateful they live so close to Rose Medical Center in the event of an emergency.

“But I’ve always dreamed of someplace,” she adds, “maybe an older community, where you have other people there that you can make friends with.”

“We are kind of on two different paths with that,” Will counters.

Growing up in Michigan, in a tiny house with lots of siblings, Will recalls how “you’d roll over and there’s a brother or somebody right next to you. Growing up, you saw somebody every minute.”

So by comparison, the Mayfair property is a slice of heaven.

Originally, he and Monetta talked about wanting a basement and an upstairs, and when the Phelpses popped the top across the street, they thought maybe that was something they should look into. But other expenses took precedence, and a second story never materialized.

I’ve always dreamed of someplace, maybe an older community, where you have other people there that you can make friends with.

— Monetta Edwards, who says she would be open to moving from her home since 1981

As for the future, it’s a question the couple is still working to sort out.

“Yeah, I guess we bump a little bit,” Will admits. “I’m kind of satisfied with this. I’d like for us to be able to do maybe a little bit of traveling, but other than that …”

He pauses for a moment.

“If the interest rates and houses were back to normal, then I think we might consider something,” Will says. “But they’re so out of sight right now.”

Perceptions of interest rates tend to shift — sometimes wildly — over time. In 1981, the average 30-year fixed rate mortgage stood at 16.63%, though it spiked to 18.63% in October of that year. But the low rates of just a few years ago — they slipped below 3% in 2021, during the pandemic — now make today’s rates in the 6% range seem positively bloated.

Still, David Corder, a 15-year housing expert who’s working with the Colorado Commission on Aging, understands where people like Will are coming from. His research has shown that perhaps the biggest housing factor facing older Coloradans at this point is affordability, plus one other factor that comes into play with declining health — design. The Edwardses may be aging comfortably into their single-level floorplan, but many older homeowners find that they need modifications to make their living space more accessible.

“And things have just gotten so expensive that they’re unable to do that,” he says. “Housing prices have gotten so high that, even if they sell their current house, they’re not going to be able to afford a smaller, downsized house at all.”

Corder has seen the ambivalence of couples like Will and Monetta at scale — Will’s desire to stay in the home weighed against Monetta’s desire for a more accommodating social setting. Wants and needs don’t always match up.

“While they are wanting to age in place, they’re wanting to find communities where they can age with others who are alike,” Corder says. “They’re wanting to find more of that social support with people around their age. They still want to be close to family, but they would rather have more community support from their own peers.”

So much … stuff

The Phelpses met while undergraduates at Colorado College — Carol from Denver, Bob from Pueblo — and when he headed to California to earn his Ph.D. in biophysics at Stanford, she joined him. After taking some classes in a graduate program, Carol figured: Why not try medical school? She was accepted at Stanford, one of seven women in a class of 100.

After seven years in California, they moved to Rochester, New York, where Bob, who found the job market for Ph.D.s lacking, opted for medical school while Carol completed her residency and gave birth to the first of their two daughters. In 1979, they returned to Colorado as newly minted physicians — Bob eventually became a professor of anesthesiology at University Hospital and Carol practiced at Kaiser Permanente — drawn back by their affinity for an outdoorsy lifestyle.

In search of a house, they found the little two-bedroom, two-bath Mayfair property. The rooms were arranged in a single-story horseshoe around a shabbily enclosed patio. But Carol walked in the front door and instantly fell in love with the living room fireplace beneath a massive mirror and exposed-beam ceiling.

Today, that room and one bedroom are the only remnants of the original house, as their expanding family required more room. They enlisted an architect and, with the very handy (and licensed) Bob doing all the electrical work, embarked on a renovation. They popped the top to a second story, expanded the ground floor and even dug out more basement space beneath the patio.

“We liked the living room. We liked the house,” Carol says. “Turns out, we really liked the neighbors.”

Carol leads visitors into a room converted into office space where the couple could work on their computers at side-by-side desks. She points to a portrait on the wall above her workspace.

“You can see my gorgeous husband right there,” she says. “And that’s our wedding photograph. We got married outdoors in Genesee Park.”

Bob’s presence is felt in more than just pictures. Carol points out that he completely remodeled this room himself, putting in a diagonal wall, recessing part of the ceiling, installing the flooring and adding everything from wallpaper to wainscotting to a coat of paint.

In this room, too, there are piles of belongings that she has not yet had a chance to sift through and filter down to a more manageable collection.

“I’ve been through some of the files and things like that,” Carol notes, “and some of his stuff and the bookshelves. But it just takes time.”

Carol’s hesitance to dive into a full-scale purge isn’t unusual, notes Joan Rogliano, a Washington, D.C.-based Realtor who relocated from Colorado. She has worked with AARP Colorado to help connect older homeowners with downsizing resources, including through webinars exploring “The Power of De-cluttering and Downsizing.”

“You’re going to give something away, you’re going to sell it, you’re going to keep it, or you’re going to dispose of it,” Rogliano says. “So it all boils down to those four choices, and once you can explain that and walk people through the resources for each of those four topics, then they feel less overwhelmed because they have a plan. And they absolutely need to have a plan.”

The generational aspect looms large, she adds. The baby boomers — she identifies herself as part of this cohort — “loved stuff.” Subsequent generations, particularly those now in their 20s and 30s, are the folks who boomers depend on to take their stuff when they no longer need it.

But those younger generations, in large part, embrace a different value set. While acknowledging exceptions, Rogliano notes that these generations tend to live smaller, prioritizing efficiency.

This story first appeared in

Colorado Sunday, a premium magazine newsletter for members.

Experience the best in Colorado news at a slower pace, with thoughtful articles, unique adventures and a reading list that’s a perfect fit for a Sunday morning.

“They don’t want 5,000 square feet. They don’t even want 3,000 square feet,” she says. “They’re looking at the climate, the environment, what footprint they’re going to be leaving. They don’t want my china. They don’t want my crystal. They don’t want my silverware because they don’t have anywhere to put it.”

For older homeowners looking to downsize, she concludes, this realization is devastating. On her webinars, tears begin to flow as she encourages them not to take it personally. It’s a tough sell.

People wonder why their kids don’t want that dining room hutch that’s been in the family for a century, or other items infused with strong emotional attachments. Don’t they have any sense of family? is a question she often hears.

As a real estate agent, she has noticed something else. Lots of boomers may be aging in place, but they’re also leaving their homes in significant numbers. She cites research showing that boomers — and especially those ages 60-69 — are dominating the market on both ends.

“A lot of them don’t want to give up their homes, because they love it, it’s safe,” Rogliano says. “They love their neighborhoods, so on and so forth. But they’re also driving the market now, because they’re the top demographic for buyers. The boomers are the ones that are buying.”

Carol feels caught in between.

“Now I’m on the fence. I’m really on the fence,” she says. “I think it would be nice to have a different place sometime, because some 45 years in one place is a long time. But I’m not ready yet.”

Daunting economics of downsizing

After he completed his military hitch, Mandell and Patricia Winter pulled together a nice down payment, showed lenders a great credit score and landed a home in the Montclair neighborhood for $37,500, with an 8% mortgage. Three years later, when his parents gave them a deal on their current home in Mayfair in 1978, they sold it for $65,000.

“It was insane,” Mandell recalls. “Just about doubled.”

The move to Mayfair came with a dose of deja vu. Mandell spent his teens under this roof, only a few blocks from Rose Hospital, where he was born. When he and Patricia, pregnant with their second son, moved in, there was plenty to do to remake the residence into something different, something that didn’t simply recall his youth.

They spent months repainting the entire house, peeling away the old carpet from the ’50s and replacing orange curtains that screamed ’70s. In the ensuing years, they finished half the basement, creating a family room. Mandell’s old bedroom became a bath and walk-in closet to complement the addition of an en suite — and eventually a covered porch, complete with hot tub.

Patricia earned an associate’s degree in interior design and put her expertise to work on the kitchen, totally reimagining the space into something more functional as well as completely their own. Yet still, Mandell would find himself thinking of something he needed to tell his mother, and going to look for her — in a house she’d vacated years earlier.

“That happened for a lot of years, when I just unconsciously was thinking they were still here,” he says. “So yeah, that was kind of weird.”

The deal they couldn’t refuse, $78,000 with debt carried by his parents at an unheard of (at the time) 6% interest, now commands a Zillow estimate in the million-dollar range. But as the couple grew older, everyday tasks like yard maintenance and negotiating the basement stairs became more taxing. Patricia has had multiple foot surgeries over the years.

Although they started looking around for alternatives, nothing made sense. Certainly not financially. If they sold, tax laws would likely put them on the hook for a sizable capital gain, even with a generous exemption. And that income bump could, Mandell fears, impact their Medicare premiums.

Downsizing isn’t an option under these market conditions, he adds. And while the state senior property tax exemption helps a bit, the annual bill has still grown to uncomfortable proportions.

Then there’s the question of where to move. Although the stairs to the laundry room in their partially finished basement aren’t getting any easier for either of them, it was a plumber’s discovery of out-of-code infrastructure — a replacement project that would run tens of thousands of dollars — that sent them looking for alternatives.

“We never found one that we liked,” Mandell says, touching on subjective criteria as varied as design and neighborhood politics.

Neither is a fan of open floor plans prevalent in new construction. In many of the cookie-cutter developments, the cabinetry seemed cheap but couldn’t be upgraded unless they moved in and ripped it out themselves. Then there was their family heirloom furniture — specifically, a massive credenza and dining room table — that nobody wants to buy, so would likely have to fit into any new dwelling.

Patricia didn’t like the idea of moving to a municipality that didn’t have extras like Denver’s availability of composting, and she couldn’t see landing in a condo-style retirement community, where some essentials, like laundry facilities, are shared.

With any luck, we’ll die here and not have to go into assisted living.

— Mandell Winter, who found multiple barriers to downsizing

“There just isn’t the kind of living situation that I want out there,” she says. “They’re all two-bedroom. I can’t live with two bedrooms. I need three. We each need an office because he’s messy, and I want my own washer and dryer.”

While the Winters’ dilemma may sound like a dream come true to younger generations faced with daunting obstacles to even considering home ownership, that doesn’t make it any less of a problem. Mandell admits their current home “is not a bad place to be stuck,” but he also gives voice to the fraught calculus of age and health.

“With any luck,” he says, “we’ll die here and not have to go into assisted living.”

His assessment at this stage likely mirrors that of many Coloradans of their generation: frustrated. A lot of that frustration stems from financial issues — like rising costs of improving their existing home and, when it comes to finding an alternative “the reality that we can’t find what we want, where we want it.”

So they look for workarounds, like reviving that bathroom remodel they considered a few years ago. Ideally, they would turn the shower stall into an area where they could fit a stackable washer-dryer so they could do laundry on the main floor.

But there’s a catch. The upgrade that seemed expensive back then now could end up costing much, much more — maybe even more than it did to remodel the kitchen. So that’s on hold, amid disconcerting chatter about the future of the country’s social safety net.

“Especially now, when we don’t know if we’re going to have Social Security,” Patricia says. “I’m not doing any remodels for a while.”

So what can keep frustrated older Coloradans from feeling stuck, and smooth the way toward the best, and most accommodating, housing situations? Burrows, the state’s senior specialist and key force behind its plan to address an aging population, figures that a lot of her work is guided by one underlying principle.

“We can create a better sense of the value that people bring to a community, regardless of age,” she says. “I think if we have a movement to reduce that ageism, we can get a little unstuck.”