How the Privy Council settled Thiruparankundram temple’s claim over its land in 1931

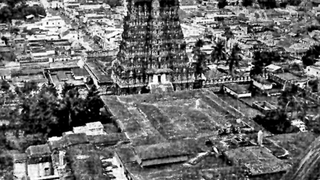

Tension has simmered at the Tirupparankundram temple, the hill abode of Lord Muruga in Madurai, amid claims of consumption of non-vegetarian food at the nearby Sulthan Sikkandhar Avulia Dargah.

| Photo Credit: The Hindu Archives

Over the past few weeks, communal and political tension has simmered at the Tirupparankundram temple, the hill abode of Lord Muruga in Madurai, in whose vicinity lies the Sulthan Sikkandhar Avulia Dargah. Amid claims of consumption of non-vegetarian food in the hills, there is also a row over the ownership of the land on which the mosque is situated. Against this backdrop, it would be interesting to see how the Privy Council had in 1931 settled the temple’s claim to the ownership of the barren hill.

Claim to Nellitope

Originally, the issue was dealt with by the trial court (subordinate judge), where the temple had claimed the whole hill, “with the exception of certain cultivated and assessed lands and the site of the mosque”, as temple property. The Mahomedan (Muslims) defendants asserted their ownership of the particular eminence upon which the mosque stands, and of a portion of the main hill known as Nellitope. The Secretary of the State claimed to be the owner of all the unoccupied portions of the hill as “Government poramboke or waste appertaining to the village of Tirupparankundram”.

In August 1923, the Subordinate Judge of Madura decided in favour of the temple, “except in respect of the Nellitope, and the actual site of the mosque with its flagstaff and flight of steps leading up to it”, which he held to be the property of the Mahomedan defendants.

Appeal in Madras High Court

While the government and the temple accepted the verdict, the Mahomedans appealed against it in the Madras High Court. In 1926, the High Court, after a single day’s hearing, while agreeing that both Hindus and Mohomedans had established certain rights to the hill, did not venture to decide what these rights were. The court, however, held that the ownership of the hill belonged to the government and dismissed the suit.

Challenging this, the temple filed an appeal before the Privy Council. In an elaborate order, the Privy Council traced the history of the temple and reference to its presence in various British-era documents. Citing the temple car procession along the ‘ghiri veedhi’ of the hill, the judges noted that the same was referred to as the ‘malaiprakaram’ (the area around the hill) of the temple in numerous documents dating back to 1844. The ‘ghiri veedhi’ housed smaller shrines and a number of old ‘mandapams’ or rest houses along with tanks and bathing places for pilgrims.

“The temples are evidently of considerable antiquity, probably dating back to the 13th century AD and possibly earlier… It is stated in a report of the Director General of Archaeology in India, which is embodied in an order of the Local Government, that the whole rock is worshipped by the Hindu community as a linga, and there seems to be some reason to believe that Madura is the home of this peculiar form of worship (Nelson’s Manual). The hill itself is frequently referred to in temple documents and also in some of the early Government records as the Swamimalai or God’s Hill,” the Privy Council noted.

Acts of ownership

The judges said that there was clear evidence for the temple authorities to have exercised necessary acts of ownership for the greater part of a century. “They have regularly repaired, and in some cases widened, the ‘ghiri veedhi’ of the passages of the temple car, removing obstructions and taking stone as required from the hill. In one case they bought and took in a house site for this purpose. The record of these works goes back to 1835 and the sums expended were at times considerable,” the Privy Council pointed out. The judges also noted that in 1861, when a claim was made to the sale proceeds of a dead tree in the hills, a complaint was made to the Collector, and the taluk tahsildar was ordered not to interfere with the “avenue of trees surrounding the Tirupparankundram hill” as they belonged to the temple.

The temple authorities had also from time to time carried out works for improving water supply to the bathing tanks, conduits, and culverts, and erected other permanent structures. A number of bridges and a mandapam were built. The Privy Council pointed out that the subordinate judge had, in fact, elaborately dealt with the evidence and concluded that these were “acts of ownership”, openly exercised by the temple authorities.

‘No interference from invaders’

Extensively tracing the temple’s fortunes in the 17th and 18th Centuries, the judges said there was no trace in the historical works to which they have been referred of any interference by the Mahomedan invaders with the sacred hill or the immediate surroundings of the temple. “They and the other predatory forces which established themselves from time to time in Madura, no doubt seized the revenue-producing lands which formed the joint endowment of all the temples, and these must have included the cultivated and assessed lands within the ‘ghiri veedhi’ but there seems to be no suggestion that the Tirupparankundram Temple or any of its adjuncts passed at any time into secular hands. It was probably during some interval of Mahomedan domination that the mosque and some Mahomedan houses were built (though the Mohamedans themselves ascribe the mosque to a much earlier period), but this was an infliction which the Hindu occupants of the hill might well have been forced to put up with; it is, their Lordships think, no evidence of their expropriation from the remainder,” the Privy Council said.

Undisturbed possession

The judges held that evidence showed that the temple was left after 1801 in undisturbed possession “of all that it now claims”. “Their Lordships do not doubt that there is a general presumption that waste lands are the property of the Crown, but they think that it is not applicable to the facts of the present case where the alleged waste is, at all events physically, within a temple enclosure. They see no reason to disagree with the Subordinate Judge’s discussion of the authorities on this question. Nor do they think that any assistance can be derived, under the circumstances of this case, from the provisions of the Madras Land Encroachment Act 3 of 1905, on which the respondent has relied,” the Privy Council said.

Consequently, the Privy Council held that the conclusion of the Subordinate Judge was right and “no ground has been shown for disturbing his decree”.

Published – February 04, 2025 11:12 pm IST