Front Range home values dip in latest property tax assessments

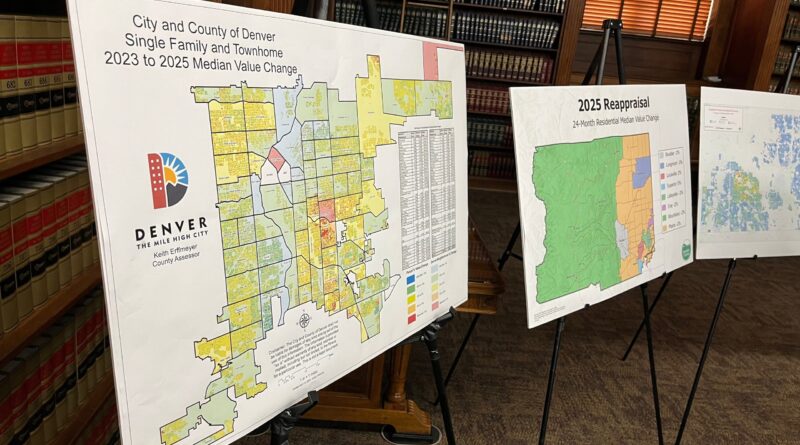

Home values across the Denver metro area largely held steady or declined in the latest tax assessment period, county assessors announced Wednesday, in the latest sign that Colorado’s housing market has cooled off from its pandemic fever.

County tax officials said it will be several months before they can definitively say whether most residential tax bills will go up or down next year. That’ll depend on whether local governments raise mill levies when they set their budgets later this year and how the state’s new property tax laws play out in different communities.

But at least one thing’s assured: The typical homeowner won’t experience major spikes in their 2026 tax bills like they did after the last re-assessment two years ago, which led to several rounds of property tax cuts at the state level.

“If there’s a headline for us in Douglas County this year, it’s breathing a sigh of relief,” Toby Damisch, the county tax assessor, said at a news conference in Denver.

In Douglas County, the median residential value dropped 3.5% in the preliminary assessments, which reflect market values as of June 2024. That’s a night-and-day difference from this time two years ago, when residential values were up nearly 50% in Douglas County, and more than 30% in Denver.

Damisch said it was the first time since the Great Recession he’s seen residential values fall in his county. And they could fall further in the coming months, when property owners have the chance to appeal their values.

Tax officials pointed to a few factors to explain the dip. High interest rates and economic uncertainty have depressed home sales in recent years. And in retrospect, the June 2022 valuation came at the worst possible time for homeowners struggling with the cost of living. Home prices peaked across much of Colorado that summer, meaning tax assessors took their biannual snapshot used to determine tax bills at the absolute height of the market.

Jefferson County Assessor Scot Kersgaard said his area was the only one to see an increase in residential values — and even there it was a minor 2% bump. Across the rest of the Front Range, home values held steady or dropped a few percentage points.

Nonetheless, housing affordability remains a major challenge across the metro area. Damisch said the cost of homeownership remains “the highest it’s ever been” in Colorado, thanks to high interest rates and insurance costs. In Boulder County, where median home values are down about 1%, prices actually went up for condos and townhomes, making it harder for entry-level buyers to purchase their first home.

JoAnn Groff, the state property tax administrator, said she won’t have numbers from all 64 counties until August, but in preliminary surveys from earlier this year, the rest of Colorado looked similar to metro Denver, with residential values mostly flat or slightly down.

But that isn’t the case everywhere. In mountain communities, where housing costs are the highest, prices are still going up. Mark Chapin, president of the Colorado Assessors Association, told The Colorado Sun that median home values are up 8% in Eagle County, where he serves as the tax assessor. In Garfield County, home to Glenwood Springs, residential values are up 14%, he said.

Along the Front Range, local governments should see tax revenue stay relatively flat, assessors said. Commercial values were up across the metro area, largely offsetting the declines in home values. Keith Erffmeyer, the Denver assessor, said growth in warehouses and other commercial properties more than made up for a downturn in the office sector, where vacancies are up as more people work from home.

Absent future tax hikes, flat tax revenue could lead to budget cuts for many local agencies, as they grapple with inflation and declines in state and federal funding.

But county tax officials insisted it was too soon to say what the valuation would mean for homeowners and local governments. In a change from previous years, homeowners won’t get an estimated tax bill with their valuation notice, due to a change in state law.

That will give counties time to determine if revenue is expected to grow faster than the state’s new property tax cap, requiring cuts to the assessment rate. And it will prevent homeowners from being given an estimate that turns out to be wrong when local government officials set their mill levy rates later in the year.

“The taxes are going to get figured out later — that’s just how it works now,” Damisch said.