‘Exterior Night’ Review: Life in Perilous Times

When the great Italian filmmaker Marco Bellocchio made “Good Morning, Night” in 2003, about the 1978 kidnapping and killing of the politician Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades, he provided a fanciful, heartbreaking coda: an image of Moro walking away from captivity, looking not much worse for wear after 55 days in a small cell.

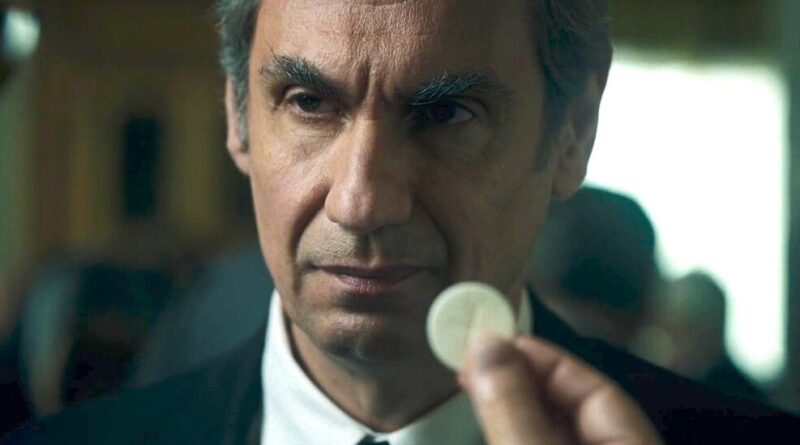

Bellocchio revisits the Moro affair in his first television series, “Exterior Night,” and once again he frees Moro (Fabrizio Gifuni) for just a bit. This time the scholarly, prickly statesman gets to stare down his colleagues in Italy’s Christian Democratic Party and tell them exactly how and why they have allowed him to die.

(Released in 2022, the series is now available in the United States on MHz Choice, where the third and fourth of six episodes will stream beginning Tuesday.)

Moro’s abduction and death was a watershed moment in the “years of lead,” when politically motivated bombings, shootings, kidnappings and assassinations convulsed Italy and other European countries. But it is a story that can speak to anyone who has a sense of living in perilous times. As a character in “Exterior Night” says, a society can tolerate a certain amount of crazy behavior, but “when the crazy party has the majority, we’ll see what happens.”

What makes Moro’s fate such prime material for dramatization, though, are its elements of mystery and imponderability and its hints of conspiracy, as murky today as they were four decades ago. Why did Moro’s own government — of which he would have become president later that year — refuse to negotiate for his release? Why did the Red Brigades finally kill him, knowing it probably would be disastrous for their cause?

“Good Morning, Night,” told from the point of view of a female captor who begins to sympathize with Moro, was a splendid film, both passionate and razor sharp. Working across five and a half hours in “Exterior Night,” Bellocchio spreads out, adding historical detail and giving space to players he had little or no room for in the film.

Bodyguards, politicians, police officers and a mysterious American “consultant” all add to the confusion. Episodes are built around Moro’s grief-stricken mentee, the justice minister Francesco Cossiga (Fausto Russo Alesi); the compassionate but dithering Pope Paul VI (Toni Servillo); and, most notably, Moro’s no-nonsense wife, Eleonora Chiavarelli (in a wonderful performance by Margherita Buy).

The expansion moves Bellocchio away from the compressed lyricism of the film, but “Exterior Night” stands comfortably on its own as an intelligent account of, and response to, the sordid events. (Bellocchio directed the series and was one of five writers.) Moving back and forth across the 55 days, he refracts the violence and the political opportunism through one set of eyes after another.

With his typical control, he is able to work the story’s wild array of elements into a lapidary whole while casually tossing off stylistic adornments. A scene in which Cossiga follows a lead into a mental hospital is a Fellini-like descent into hell. The fruitless efforts of the understaffed police and self-important military are given a subtle edge of slapstick. Smart political intrigue in the style of Costa-Gavras merges with rich family melodrama.

For most of the series, Moro himself exists as a kind of ghost, present in the guilty dreams and fearful visions of others. Then he is suddenly present, in a confessional scene based on an apocryphal incident said to have taken place during his captivity. It is shot simply, in the harshly lighted confines of Moro’s enclosure (both film and series suggest the commonality of the prison cell and the confessional booth), and Gifuni is splendid as Moro pours out his anger and despair, aghast at having misplaced his faith.

Now 85, Bellocchio is certainly among the world’s best living filmmakers; “Exterior Night” may not sit with his very best films (like “Fists in Pocket,” “China Is Near,” “Good Morning, Night” and “Vincere”), but it fits seamlessly into an astonishing body of work. More astonishment: Max just announced its first original Italian drama, “Portobello” — directed by Marco Bellocchio. A reason to look forward to 2026.