Trey Helten, prominent advocate for drug users, has died

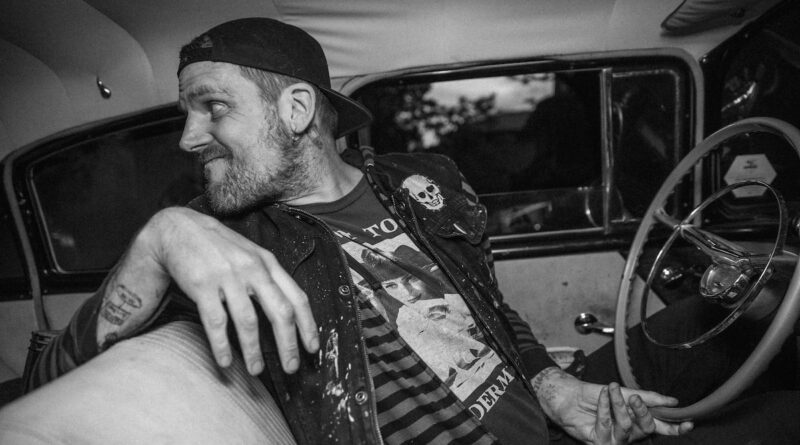

Trey Helten drives his vintage Chevy Bel Air through Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.Jackie Dives/The Globe and Mail

Trey Helten, an advocate for drug users whose willingness to speak searingly about his own battle with addiction provided hope and inspiration to many in Vancouver’s troubled Downtown Eastside, has died. He was 42.

His cause of death was not immediately known.

For many years, Mr. Helten’s official title was manager at Vancouver’s Overdose Prevention Society (OPS), where he had worked his way up the ranks since first volunteering there close to a decade ago. But the title did not capture the extent of his efforts and the impact he made on some of the city’s most vulnerable.

He would facilitate Narcotics Anonymous meetings a few times a week, attracting skeptical peers with tales of his own successes and setbacks. He bought food for those who couldn’t afford it. When someone chose recovery, he drove them to detox, day or night. He helped people schedule medical appointments and find housing.

He reversed hundreds of overdoses and trained others to do the same. He has shared his time and extensive knowledge of substance use with local journalists trying to make sense of an unabating crisis.

“I can’t think of another person whom a list of people could credit for them being alive,” said Chris Ferguson, a Vancouver movie producer who had been working with Mr. Helten on various projects.

And when people died, as they did one after another as the illicit drug supply grew increasingly volatile, Mr. Helten planned memorials for those who had no one else.

OPS executive director Sarah Blyth said his death is an enormous loss to the Downtown Eastside.

“There was no one as dedicated as him,” she said through tears on Wednesday.

Opinion: Living and dying through B.C.’s overdose crisis

Mr. Helten had been open about his demons. In earlier interviews with The Globe and Mail, he spoke candidly of a deep self-loathing dating back to childhood. He self-medicated with drugs and descended into addiction and homelessness for most of his 20s and some of his 30s before finding the rocky road to recovery.

In April, 2021, The Globe profiled Mr. Helten as he marked five years of being drug free. While others celebrated the milestone, he said he was uncomfortable with the praise because he was no poster child. He carried a white key tag – a token typically given to people attending their first Narcotics Anonymous meeting – as a reminder to take things day by day.

Last May, he told The Globe that he had hit a rough patch. A relationship had fallen apart, he had stepped away from work at OPS, he was in hospital with pneumonia and had relapsed. Walking along Vancouver’s East Hastings Street had suddenly given him deep feelings of stress and anxiety.

Mr. Helten folds his laundry in his room with his two pets, Zelda and Chico, in Vancouver.Jackie Dives/The Globe and Mail

But he seemed to bounce back, again. He resumed work at OPS and facilitating Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He got a new job as a body-retrieval agent for the BC Coroners Service, telling friends that it brought him comfort to “bring friends to their final destination” in a dignified way. He told The Globe that his work was his recovery.

Amanda Rose, Mr. Helten’s partner, who is three months pregnant, said he struggled with recovery over the past year. He was haunted by the immense loss he faced in his line of work, and struggled personally with the guilt and shame associated with being a drug user.

Ms. Rose said Mr. Helten was seeing a therapist regularly, but sought more intensive trauma counselling that seemed out of reach.

“Doing this type of work, especially at the level that Trey did, is a massive emotional undertaking and there isn’t a lot of meaningful and affordable trauma counselling available,” she said. But she was proud that he kept trying.

Guy Felicella, a harm-reduction and recovery advocate, said he and Mr. Helten had spoken about trauma counselling a few months ago. Mr. Felicella said some counsellors offer a sliding scale, but Mr. Helten said it would still be too expensive.

Mr. Felicella said his friend was at his best when he was helping others, but that he struggled with helping himself.

“This work is very, very hard and it can be very traumatic to deal with,” he said. “Unfortunately, he only sought relief from trauma because he couldn’t heal from it for many reasons. And one big one was because he couldn’t afford it.”

Mr. Helten films a video with his friends in Vancouver’s DTES. Mr. Helten was always trying to bring the community together to work on creative projects, particularly ones that will make people laugh.Jackie Dives/The Globe and Mail

Nathaniel Canuel, a videographer who quickly became close friends with Mr. Helten after volunteering at OPS in 2019, shared Mr. Felicella’s assessment.

“The only thing that made him feel good was helping people,” he said. “Otherwise, he was in his own turmoil.”

Mr. Helten had recently signed on to facilitate recovery meetings at OPS that would be an evidence-informed take on traditional Narcotics Anonymous gatherings. He had been scheduled to participate in training on Tuesday morning but failed to show up.

When he didn’t answer his phone, Ms. Blyth and a colleague went to his home in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood, where they would learn that he had died. He leaves behind a son.

Mr. Helten’s body was retrieved by the people who had trained him.