Concerns mount among Ontario health care providers about planned closure of supervised drug use sites in March

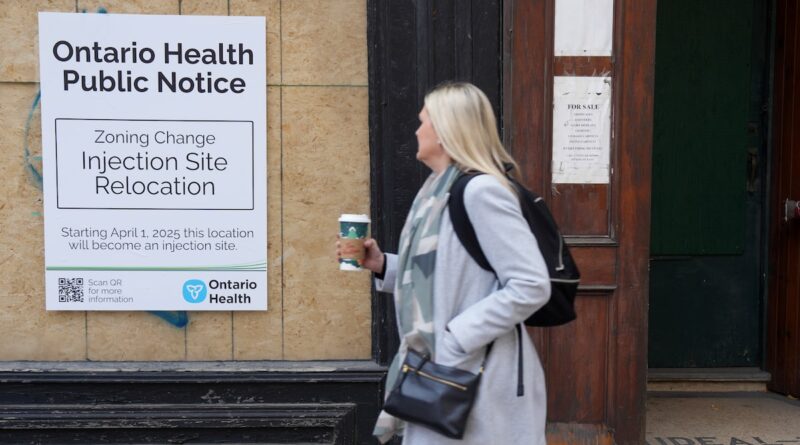

Posters appear next to a doorway in Toronto to highlight opposition to the Ontario government’s proposed closure of supervised consumption sites, on Nov. 25, 2024,Chris Young/The Canadian Press

Medical professionals in Ontario are warning that overburdened emergency rooms will be further strained should closings of supervised drug-use sites take effect by the end of next month.

The provincial plan to shutter supervised drug-use sites, where individuals can use unregulated substances in the presence of trained workers who can respond to overdoses if needed, was ordered by Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s government last year.

The legislature passed the Safer Streets, Stronger Communities Act in December. It prevents municipalities from applying directly to the federal government to open any new drug-use sites and prohibits any of them located within 200 metres of schools and child-care centres.

The plan will result in 10 of the province’s 23 sites being shuttered. The decision drew ire from health advocates who fear the closings could lead to additional fatalities in an opioid crisis that killed more than 2,500 people in Ontario in 2023.

In response to the criticism, Mr. Ford has defended his government’s intentions and has called supervised drug-use sites the “worst thing that could ever happen to a community.”

The closings now appear to be moving closer to reality. Public-opinion polls show that Mr. Ford’s party has a strong chance of returning to power when Ontarians head to the polls next Thursday. This has contributed to heightened concerns about the fallout for the health care system and staff who are already overwhelmed by demands.

Erin Ariss, a registered nurse and provincial president of the Ontario Nurses’ Association, said Thursday that her union is alarmed about the prospect of supervised consumption sites closing. The decision will place vulnerable individuals at greater risk, she said.

“Some will die of overdoses in the community, many others will be taken to already-overburdened emergency departments,” Ms. Ariss said in an e-mailed statement to The Globe and Mail.

“This will further overwhelm hospitals that are already struggling with patient caseloads.”

ONA and other organizations representing health care professionals issued a joint statement last year voicing their strong opposition to the government’s announcement.

Toronto Public Health warned in January that a reduction in services poses “a significant risk of increased overdose deaths” because the alternative to supervised drug-use sites is for people to use drugs alone in potentially unsafe environments. It noted how sites are located in neighbourhoods that see a high volume of calls to paramedics about suspected opioid overdoses.

The shuttering of supervised drug-use sites has come up in the context of the provincial election campaign, such as during a debate held in Northern Ontario. But it has not been a central focus of the race. Mr. Ford has largely tried to pitch voters on his belief that he is best suited to respond to U.S. tariffs and President Donald Trump.

At a media event held in Clarence-Rockland, located east of Ottawa, on Wednesday, Liberal Leader Bonnie Crombie said supervised drug-use sites are needed, but they should not be located “anywhere near schools or daycares, playgrounds, frankly even on main streets affecting business.”

Ms. Crombie, who has been public about her biological father’s struggles with addiction, did not provide specifics when asked where she believed they could in fact be located. “It’s not easy to find the right location, but it is necessary,” she said.

Harm-reduction strategies have received growing political scrutiny in Canada, including over the issue of safety. Ontario’s plans to close the sites were announced in the aftermath of the death of a 44-year-old mother hit by a stray bullet outside the South Riverdale Community Health Centre in east Toronto in 2023.

The province’s decision echoes an approach taken in Alberta in 2021 in response to similar concerns. Federally, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has promised to yank funding from the sites, which he calls “drug dens.” He has said he would instead direct money to addiction-recovery programs if his party forms government after the next federal election.

Mr. Ford has announced that his party is pursuing a different approach: the creation of 27 addiction recovery treatment hubs. Health Minister Sylvia Jones said last month that the hubs will provide access to mental-health support, addictions care, primary care, supportive housing and employment services.

Advocates for supervised drug-use sites have pointed to internal government reports highlighting that the sites are crucial for preventing deaths. When asked about these reports, Ms. Jones has said: “We’re listening to parents; we’re listening to individuals who have had to deal with this on a day-to-day basis.”

With reports from Laura Stone