At 90, the Ghanaian Highlife Pioneer Ebo Taylor Finds a New Voice

Jazz Is Dead initially brought Taylor to the United States in 2022 for his very first American shows. The singer and actress Janelle Monáe was among those who attended his concert in Los Angeles at Lodge Room that year. She’d first been turned on to Taylor by the Ghanaian producer Nana Kwabena, who worked on Monáe’s 2023 album, “The Age of Pleasure.”

“‘Love and Death’ was the first song I heard, and I was floored,” Monáe wrote in an email. “It’s one of my favorite songs ever made. It scares me and yet articulates a feeling I have but couldn’t quite express.” Monáe said she cried and danced at the show in Los Angeles. “Seeing Ebo perform at this stage in his life deeply touched me. I felt like I was watching a mystic time traveler who had a lot to tell us about life.”

Taylor’s 2022 shows went so well that Younge proposed recording immediately after the short run of dates concluded. “To see how people responded, I got excited like, ‘What if we recorded a new album with Ebo on analog tape with real instruments and did something sonically that was raw but looking back at yesterday for tomorrow?,’” he recalled.

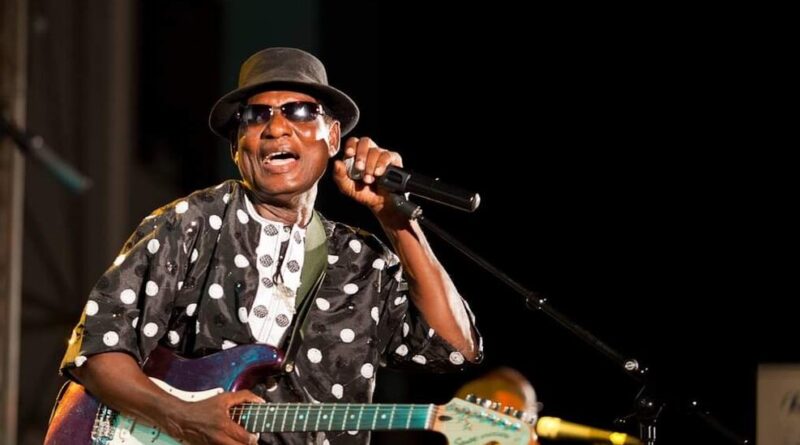

Taylor is often credited with incorporating advanced jazz chords and deep funk rhythms into traditional highlife music, but these days, he can no longer play guitar — as Henry put it, “All his fingers won’t comply” — and his voice, once a sweet, mellifluous instrument, is raspy and labored. Rather than try to hide the musician’s new reality with production tricks, Younge and Muhammad leaned into it.

“I wanted to attack this the same way Ebo might’ve attacked this in his 20s,” Younge said. “Seeing him onstage, there was a very particular charm I got from his vocals, a bravado, something very unique. I wanted to own that. It’s that punk rock approach versus the smooth jazz way of doing records from older people. Ebo’s voice wasn’t anything to shy away from. It was the absolute center point.”

On the lively opening track, “Get Up,” Taylor’s deep, haunting vocals cut through a frenetic swirl of horns, synths, guitars and skittering beats. Amid the swaggering bass lines and stuttering guitar riffs that underpin “Kusi Na Sibo” and the hypnotic “Nsa a W’oanye Edwuma, Ondzidzi,” Taylor sings as if offering an ancient incantation. In other spots, the gravelly, guttural tones in his voice feel like a dynamic counterpoint to airy melodies and buoyant rhythms, regardless of whether he’s singing in English, as he still does occasionally, or in his native Fante dialect of Akan.